Abstract

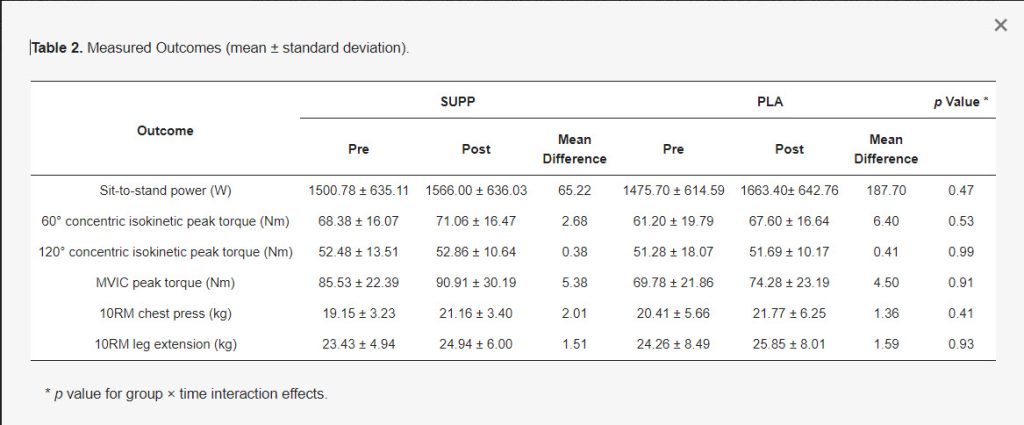

Breast cancer is prevalent in the US, with survivors facing muscle mass and strength declines. Creatine boosts strength in older adults, but its impact on cancer survivors is unclear. This study examined 19 female survivors (average age: 57.63 years) taking either creatine or a placebo. After a week of supplementation, tests showed no significant difference in muscle performance between the groups. This suggests that short-term creatine use doesn’t enhance muscle performance in breast cancer survivors.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer treatments often lead to declines in muscle mass and strength, exacerbating physiological and cognitive challenges. Creatine, known for enhancing energy production during exercise, shows promise in countering these effects. While extensively studied in other populations, its efficacy in oncology remains largely unexplored. We aimed to assess the effects of short-term creatine supplementation on muscular performance among breast cancer survivors. We hypothesized improvements in lower-body power and strength following a 7-day regimen of 20g creatine monohydrate.

2. Methods

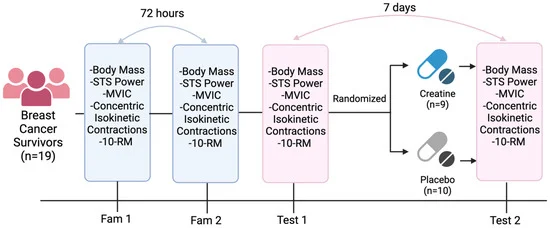

2.1. Experimental Approach

This study employed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design to assess the effects of short-term creatine supplementation on muscular performance in breast cancer survivors. Data were collected at the Exercise Oncology Laboratory, University of South Carolina. Participants underwent two familiarization sessions, spaced at least 72 hours apart, before any experimental condition, aimed at familiarizing them with the testing protocol and minimizing practice effects. Tests included sit-to-stand power, balance, chair stand, gait speed, timed up-and-go, and 10 repetition maximum (10RM) for chest press and leg extension. Knee extensor isometric and concentric isokinetic strength were also assessed using an isokinetic dynamometer. Testing battery time was standardized within participants. Random allocation (1:1 ratio) to treatment (creatine) or placebo groups occurred after the first experimental session (T1), conducted by a blinded team member using an online randomization generator. Participants and study staff remained blinded to group allocation.

2.2. Participants

Nineteen women in Columbia, South Carolina, who had been treated for breast cancer, were recruited for this study through flyers at local oncology centers and cancer-related events. They filled out an online form about their health, supplement use, and exercise history. Those actively undergoing cancer treatment, unable to reach the location, or taking creatine were excluded. Also, individuals with health conditions like previous injuries, heart problems, or bone metastases were not included due to safety concerns. Participants who were interested and met the criteria gave informed consent. The study was approved by the University of South Carolina’s Institutional Review Board (Pro00119366).

2.3. Sit-to-Stand (STS) Power

This study used a chair and a linear transducer to measure Sit-to-Stand (STS) power. Participants practiced before the test. They wore a belt connected to the transducer and sat in the chair with arms folded. Markings were placed at their feet for consistency. Participants stood up quickly and sat back down. The transducer calculated power based on vertical velocity and mass moved. The test was done three times with breaks, and the highest peak power value was recorded.

2.4. 10 Repetition Maximum Strength

Participants underwent strength assessments for both upper and lower body using the chest press and leg press machines, respectively. They began with a full-body warm-up followed by specific warm-up sets on each machine, gradually increasing the load towards their anticipated maximum weight they could lift for 10 repetitions (10RM). The specific warm-up sets comprised 4-6 repetitions at increasing loads with rest intervals of 90-180 seconds. Then, participants attempted the 10RM, aiming for the maximum weight they could lift with proper technique for 10 reps. Multiple attempts were allowed with sufficient rest until the correct technique couldn’t be maintained. The highest weight lifted with proper form was recorded as their 10RM.

2.5. Maximal Voluntary Isometric and Concentric Isokinetic Knee Contractions

The study measured the maximum strength of knee extensors using a Biodex System 3 isokinetic dynamometer. Participants sat with their dominant knee secured and performed tests with their knee starting at 90° and extending to 160°. They did five repetitions at two speeds (60°/s and 120°/s) aiming for maximum torque. Peak torque values achieved were recorded. Afterward, participants did three five-second maximum voluntary contractions with the knee flexed at 120°. The highest peak torque from these attempts was recorded. These tests are common for assessing knee strength in various populations.

2.6. Supplementation

Participants were divided into two groups, one receiving creatine (SUPP) and the other receiving a placebo (PLA). The allocation was done by a team member not involved in the assessments, using coded envelopes to keep it blinded. Neither the researchers nor the participants knew which group they were in until after the analysis. The SUPP group took 20 g/day of creatine powder for 7 days, while the PLA group took dextrose powder. This dosage was chosen based on previous research showing its effectiveness. To minimize stomach issues, participants took 5 g doses four times a day with fruit juice. They received reminders via text messages. Compliance was monitored by checking returned empty packets.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) to show the data. We analyzed changes before and after using a two-way mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) for variables like body mass, sit-to-stand power, knee extensor strength, chest press, and leg extension. Group (supplement or placebo) was a factor between subjects, while time (before and after) was within subjects. If there were significant interactions or main effects, we did Bonferroni-corrected comparisons. We considered results significant at p < 0.05. We also calculated effect sizes using Cohen’s d (for comparisons) and partial eta squared (ηp2 for ANOVAs). Values of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 for Cohen’s d were small, medium, and large, respectively, and 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 for partial eta squared. We used JASP software for analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

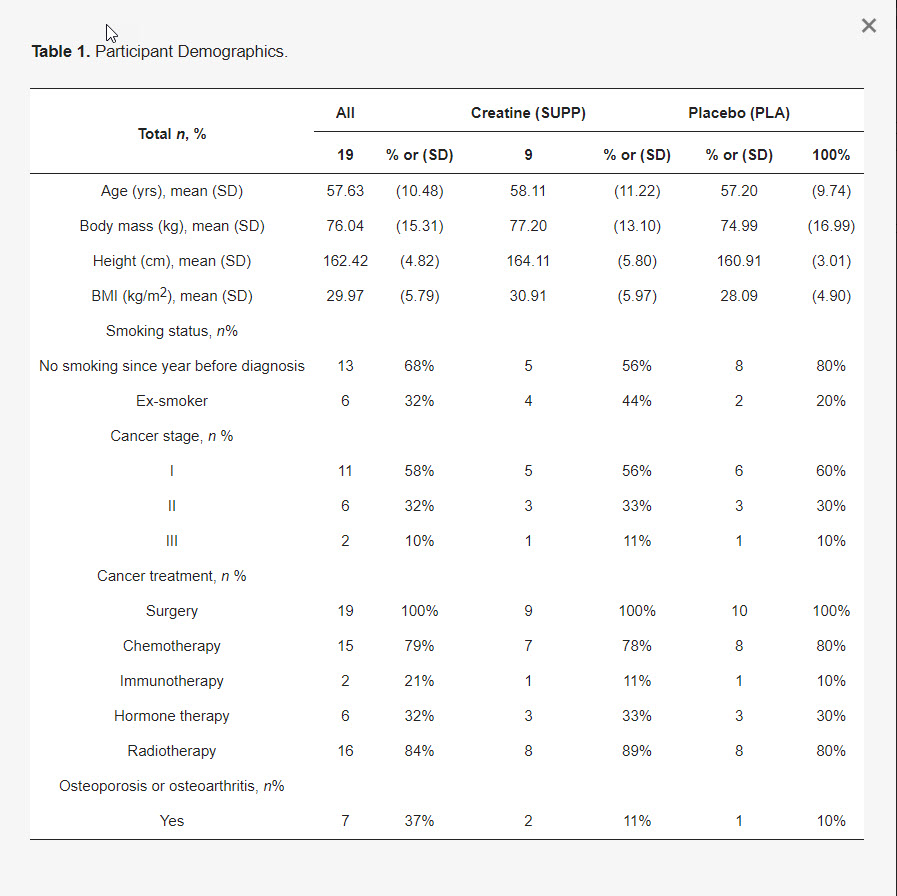

Nineteen female participants, with an average age of 57.63 years and BMI of 29.97 kg/m2, completed the study. Most were White (79%), with smaller percentages of Asian (5%), Black (11%), and Hispanic (5%). Majority were at stage I (58%) followed by stage II (32%) and stage III (10%), with an average time since diagnosis of 35.37 months. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Both groups were similar at the start. Table 2 presents pre-post values and mean differences within groups.

This simplified summary was generated by AI from the original article.

Reference:

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/7/979